Shell Scripts 2: Script utilities

OR… on writing a clear, consistent and simple script utiltiy.

Last month, we developed a toolbox of basic good software engineering principles in Shell Scripts 1: Bourne back again. We’ll apply the same approach to creating a robust utility script template that parses and validates common command line option patterns, produces colored output, and has a common color and validation implementation with testing.

At the end of this article, you will understand how to design solid command line driven scripts and have templates to use as boilerplate for your own scripts.

NOTE: You can clone the source here, and use the start_test_env.sh script to setup an Alpine Linux test environment to play along as you read.

Command line utilities

Command line utilities have a user experience; we want to replicate that so our scripts feel like every other command line utility - a polished and familiar presentation.

A “command line utilty” is very different than a “command line application”. A command line utility like echo or tr provides a couple of single character options with perhaps some operands. Even the advanced functionality of grep takes only single character options and option arguments and operands.

Note that I am using POSIX names option and operand for the older names flags and positional arguments.

In contrast, a “command line application” like docker or kubectl has global options, single character and long form options with required and optional options, required and optional operands, and sub-commands that may take distinct own options and operands, that overlap with other sub-commands AND may inherit global options AND may propogate their distinct options to other sub-commands.

Our scope in a shell script is a “command line utility”. You can write a pretty complex bash script that does many “command line application” things, but if you operate at scale, you are not doing anyone any favors. You are creating an operational and maintenance money pit. When you find needed functionality approaching something like docker, you are much better off using golang and the Cobra library. Creating shell utilities in Go is simple enough for anyone brave enough to attempt it, especially using a framework like Cobra. The language and framework will provide robust tools for testing and validation

Since we always start with design, let’s figure out how to describe how to use our utility to our users - taking our cues from the sh built-in getopts and common command line utilities like grep.

Note sh’s pluralization of the Gnu facility: getopts vs. getopt.

Syntax

The IEEE Std 1003.1-2017 (POSIX.1-2017) utility syntax formalizes command line utility syntax which can be summarized as:

script.sh [-ab] -c arg [-d arg] [-e arg]... [operand...]

Option descriptions:

1. [-ab] : Optional options.

2. -c arg : Required option-arg pair.

3. [-d arg] : Optional option-arg pair.

4. [-e arg]... : Zero or more '-e arg' pairs.

5. [operand...] : Zero or more operands.

NOTE: Although included in the POSIX spec, mutually exclusive options, [-a|-b], and optional option-arguments, -f [arg] and [-f [arg]] are not directly supported by getopts. The first could be implemented in parsing logic with getopts, the second would require using getopt or implementing your own logic. Both options require a lot of extra code, extra testing and maintenance cost, and complexity for the user. Instead, reconsidering your option design will likely produce a cleaner result.

Option and Operand Arity:

| Syntax | Description |

|---|---|

[-f arg]... |

specifies 0 or more option-argument pairs |

-f arg [-f arg]... |

specifies 1 or more option-argument pairs |

[operand...] |

specifies 0 or more operands |

operand [operand...] |

specifies 1 or more operands |

There are some other advantages to using the getopts built-in. First, it is cleaner code. Being a built-in, getopts can set shell variables to use for parsing - impossible for getopt or any external program. Second, it was chosen for POSIX compliance. In the IEEE Std 1003.1-2017 (POSIX.1-2017), regarding getops: “The getopts utility was chosen in preference to the System V getopt utility because getopts handles option-arguments containing

The above option syntax provides all the functionality you need for a command line utility. If are designing a script and the rule is not listed, first check your design to see if it seems convoluted and you could refactor to fit into these simple and familar examples above. If not, review the IEEE standard link above to see if they offer some advice. If you are still looking for an elegant solution, perhaps you have exceeded the intent of a small utility script and should be looking at golang and Cobra mentioned above.

Standards are good, not necessarily because of their content, but because they are “standard”.

I have seen many scripts that use options, option-arguments, and operands to simply get information into the script without regard to semantics and consistancy. Creating a great UX means effortless and clear communication with the user - a standard approach. Let’s talk through the argument syntax described above so we can be very intentional when we communicate in that language.

Boolean options

A bare option like -b is boolean in nature, it turns a feature on or off by its presence or absence. Your calling convention should omit the option for expected use cases and use the option to change default behavior or add functionality. For example, most people expect a script to just do its job. But less frequently, they want more details about what the script is doing or want it to perform an additional task:

# Usage: script.sh [-vo]

# Do your standard job

./script.sh

# I don't understand what your are doing, be more verbose

./script.sh -v

# Do your standard job AND that other thing you do

./script.sh -o

# Do your standard job AND that other thing you do AND give me

# all the gory details

./script.sh -o -v

./script.sh -v -o

./script.sh -ov

./script.sh -vo

Communication notes:

- The option name indicates the infrequent mode and is the first character we will use in the help screen to describe the option making the command options easy to remember.

- Because bare options are boolean in nature, it doesn’t make sense to have a required bare option - no information is conveyed; it can only be value=1.

-b...and[-b...]are nonsensical - they are boolean in nature so having more than one provides no informaiton.- Boolean options can be specified in long form:

-b -cor short form:-bc.

Key-value options

Options with arguments like -f arg, are key-value in nature; the option provides the context to understand the option-argument.

There are two forms: required and optional. When required, the script needs the information to do its job. When optional, the option can turn on or off additional functionality, as with a boolean option. The option-argument provides either an enum to clarify the additional functionality, or data to operate on.

# Usage: script.sh -f infile [-o outfile] [-v verbosity_level]

# Process this file and print to stdout

./script.sh -f file

# Process this file and write output to outfile

./script.sh -f file -o output.txt

# Process this file and write output to outfile AND be very verbose

./script.sh -f file -o output.txt -v debug

Communication notes:

- The option name indicates the additional functionality or infrequent mode and is the first character we will use in the help screen to describe the option making the command options easy to remember.

- Use common options for common meanings:

-h: help-f: input file-o: output file-c: config file-q: quiet mode - essential for automating your script if you print info/errors to stdout-v: verbosity

- You may find times where you want the option to have an optional option-argument. Perhaps you want to have

-vturn on error reporting and-v debugbe very verbose. Optional option-arguments are not supported bygetopts. Instead use an enum as in the example above, or perhaps separate options if that is similarly clear to the user.

Operands

Operands are bare word script arguments - they don’t use options as keys to identify context. There are several ways we can communicate use:

| Usage | Description |

|---|---|

script.sh [-hv] |

No operands. |

script.sh [-hv] operand |

1 required operand |

script.sh [-hv] operand [operand...] |

[1..n] operands |

script.sh [-hv] [operand] |

1 optional operand |

script.sh [-hv] [operand...] |

[0..n] operands |

Operands should be the same semantic type and unordered. Consider the following example:

# Create an account from required positional args

./create_account.sh user_name first_name last_name email

Even if this is documented well, users will never keep the order straight and have to look at the doc. It will also be difficult to debug when users have problems - meaning that you can’t see the problem on inspection. When they misuse this script, there is a maintenance cost to fixing the broken account. If you could write a validator that could tell first_name from last_name, for example, it is extra implementation cost. It is far more clear to make these key-value options.

Communication notes:

- When writing your script, take the time to design your command line syntax; write the usage (syntax), option description and the rest of the help screen first to clarify the design in your head. As you implement and discover problems, revise the help screen first to help clarify your design. That time is easily reclaimed at implementation time, and avoiding support calls.

- You could use operands as sub-commands. If you reach the script complexity that requires sub-commands, you would probably be better off using golang and the Cobra/Viper library.

Parsing script arguments

The getopts built-in has a simple option syntax and can handle any of the following calling conventions:

Usage: cmd [-ab] -c arg

given: getopts 'abc:', getopts will handle the following arg syntax

cmd -abcarg file file

cmd -a -c arg file file

cmd -carg -a file file

cmd -a -carg -- file file

Note the -- in the last example. This signals an end to boolean and key-value options and that all remaining arguments are operands. This convention is required if the first operand has a leading - so getopts can tell it is not an invalid or duplicate option.

Parsing options

Finally! Some code! Let’s start implementing all that we have talked about.

This is the standard form of getopts use:

# Usage: script.sh -i int [-htf] [-v enum] [-s string] [-l string]... [file...]

while getopts "i:htfv:s:l:" OPT; do

case ${OPT} in

h) ## -h help

show_help

exit 0

;;

# ...

esac

done

There is a lot going on here - let’s break it down a bit. The first arg to getopts: "i:htfv:s:l:" defines acceptable options. If a colon follows the character, that option has a required argument and getopts will throw an error if one is not provided. You can use any alpha-numeric character as an option.

Note that there is no indication of required or optional options; that is provided in your usage statement and up to you to enforce in argument validation.

The while .. do control flow calls getopts for each trip through the loop, setting the next getopts argument, OPT, to the current option character. getopts also sets ${OPTARG} to the option-argument, if supplied, and ${OPTIND} to the index of the command line argument being processed.

The next line starts a case block that will hold have a section for each option. The h option shows help and exits successfully.

Each option in the getopts option string (i:htfv:s:l:) will have it’s own section in the case block, which, of course, varies script to script.

The last block in the case is the “default” handler - something to catch options that getopts thinks are valid, but that we didn’t handle - a code flaw. I always include this to catch maintenance injection errors - someone altered the getopts option string and the case is missing.

*) ## Unhandled option

## Using getopts, this only happens when a character in the getopts string

## does not have a case in this block - it is a code flaw - fix it.

error 'Congratulations! You have discovered a bug. Please copy this error information'

error 'and create a GitHub issue so it can be fixed.'

error "Unhandled option: OPT = '${OPT}', OPTARG = '${OPTARG}', OPTIND = '${OPTIND}'"

error "Command line: ${CMD_LINE}"

exit 4

;;

esac

done

Look at all the information in that block! It informs the user that he has found something really interesting, tells them to create a GitHub issue and prints all the information that should be included. It also contains enough information that anyone that picks up the issue should be able to fix it. With all of this information, the bug should get reported and I won’t be the only one that can fix it.

Parsing operands

The above case block handles all of the script options. Now we need a post-processing block to implement some more argument parsing and validation. Back in our “Usage” statement, we advertise that we can handle [0..n] operands - this is how:

# Extract operands. Note: prior to this statement, ${@} had not been modified

# Note: the $(( )) shifts into math mode

shift $((${OPTIND} - 1))

OPERANDS="${@}"

${OPERANDS} will hold everything on the command line after the last option-argument pair.

This needs a little explanation. As background, the set function takes a list of “words”, sets ${@} to the contents of the whole list, and allows access to any of the words by index, e.g. ${1}. When your script starts, set is applied to the command line; it is the reason we can use ${0} in our directory locator to identify our script name: that is the zeroeth entry:

THIS_SCRIPT_DIR=$(dirname $(readlink -f "${0}"))

getopts uses this facility to navigate the command line args; each call moves ${OPTIND} and ${OPTARG} to the next option argument pair (implies handling options without arguments). When getopts reaches the last option, indicated by an argument without a leading - or just a bare --. That’s when we exit the case block.

The shift function manipulates ${@} and the indexed values ${1}, ${2}, etc. When called, shift removes ${1} from ${@}, updates ${1} to point to ${2} and fixes up remaining index global variables similarly.

If shift is given an integer argument, it will shift that many items from the front of the ${@} list and fix up indexed entries. The shift $((${OPTIND} - 1)) line uses this to remove all options and option-argument pairs from ${@}.

Note: ${@} and derived index variables have a shell level scope. They are initialized from the command line and you really don’t want to modify them before command line processing. But, the set facility is pretty useful, and you may want to use it during command line processing. Because of the shell level scoping, this is easy: wrap your set call with ( ) to create a subshell, or put the set call in a function - an implied subshell. More on that in the next article.

Storing parsed data

In more complex scripts, we will want some variables to hold the parsed options or the argument parsing while-case block will quickly become unmanageable. To avoid a simple script growing into a monster, I always provide a set of option and argument variables: if I set the pattern, others will follow it.

# Set defaults for all command line arguments: 0=on, 1=off.

# Command line parsing will update these to match caller's desires.

I_OPTION=1

I_VALUE=

F_OPTION=0

L_OPTION=1

L_VALUE=

# ....

These variables also provide a chance to set default variables. For each option that takes an argument, if you provide both an option and value variable, you can set defaults for both and easily tell if the user has specified an argument twice - usually a caller mistake that will be difficult for them to identify.

You can check out the source code to see the bigger picture.

At this point in our script, all the options and operands have been parsed and stored in variables. A great UX will prevent users from misusing the script and provide useful feedback to help them get it right. The first step is validation.

Argument validation

getopts provides some option validation. If the caller does not provide a required option argument:

# ./script.sh -i

No arg for -i option

If the caller specifies an unknown option:

# ./script.sh -z

Illegal option -z

As we noted above, the getopts option string allows you to identify acceptable options and whether they should have an argument. It doesn’t let you say that some options are required, that some should never have duplicates, or that duplicates are OK, or really any other validation.

We want a great UX and this is pretty meager validation. We can do better. If we focus on helping the user as much as possible, we might want to tell them:

- which option had the problem,

- when the argument type is wrong,

- if they missed required options,

- if they specified an option twice,

- if the combination of options doesn’t make sense,

- and color the errors so they are easily identified.

Basically, we want to show enough information that the user doesn’t have to mine help to try to figure out what went wrong. Since we are going to all that trouble, let’s turn off getopt’s validation and improve on that as well. If the first getopts option string is :, it goes into silent mode; recognizing errors and not reporting them. From the utility_example.sh script:

# Usage: ${0} -i int [-htf] [-v enum] [-s string] [-l string]... [file...]

while getopts ":hv:tfi:s:l:" OPT; do

case ${OPT} in

# ...

Let’s take a look at how we can validate option arguments while we parse them:

i) ## -i integer, required, default = none

getopts_info '-i'

if is_int "${OPTARG}" ; then

if [ "${I_OPTION}" = "0" ] ; then

duplicate_option_error 'i'

else

I_OPTION=0

I_VALUE="${OPTARG}"

fi

else

arg_type_error 'integer'

fi

;;

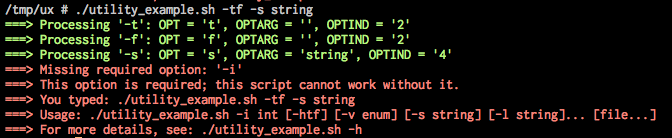

The first line in the block, getopts_info '-i' calls a local function for debugging:

# Print developer diagnostic information - for debugging

# and, because this is a demo.

getopts_info() {

if is_msg_allowed 'debug' ; then

stderr "$(green "===> Processing '${1}': OPT = '${OPT}', OPTARG = '${OPTARG}', OPTIND = '${OPTIND}'")"

fi

}

This reads pretty well: if debug messages are allowed, then print a green message to stderr. is_msg_allowed is a local function that checks the -v option to see what level of verbosity was requested. The stderr and green functions were sourced from colors.sh which we will dive into shortly. Output for this option looks like:

/tmp/ux # ./utility_example.sh -i1

===> Processing '-i': OPT = 'i', OPTARG = '1', OPTIND = '2'

The next line: if is_int "${OPTARG}" ; then uses the return code from the is_int validation function from validation.sh which looks like:

# Return true (0) if arg is not empty and an integer, false (1) otherwise.

is_int() {

printf "%s" "${1}" | grep -qE '^(\+|-)?\d+$'

}

This function safely prints ${1}, the "${OPTARG}" it was passed, and pipes it to grep. If the regex doesn’t match input, grep will have an exit code 1 that will become the function return code. If the arg is not a valid int, we print an arg type error and exit, otherwise we can move on to the next validation.

Because our option variables include both I_OPTION and I_VALUE, we can easily test if the option has been set before on the nested if block:

if [ "${I_OPTION}" = "0" ] ; then

duplicate_option_error 'i'

else

I_OPTION=0

I_VALUE="${OPTARG}"

fi

If the option has already been set, the duplicate_option_error will print the following:

===> Duplicate option: '-i'

===> This option does not support multiple values; this script cannot

===> tell which option value you intended.

===> You typed: ./utility_example.sh -i 9 -i10

===> Usage: ./utility_example.sh -i int [-htf] [-v enum] [-s string] [-l string]... [file...]

===> For more details, see: ./utility_example.sh -h

If both validations pass, we set / assign our variables.

The rest of the options are variations on this theme, so, let’s turn our attention to improving getopts standard error reporting.

When getopts is in silent mode, it sets ${OPTARG} to ? for invalid options and : for missing required option arguments. We can add blocks to our option parsing case block to handle this:

\?) ## invalid option, set by getopts during intial cmd line parsing

## OPTARG = invalid option character

## NOTE: in verbose mode, OPTARG is unset

syntax_error 'Invalid option'

;;

:) ## missing required option-argument, set by getopts during intial cmd line parsing

## OPTARG = option character missing required arg

## NOTE: in verbose mode, OPTARG is unset

syntax_error 'Missing required argument for'

;;

The local function syntax_error provides the user feedback:

# Print a command line syntax error in red

# ${1} : error type

# Note: this can only be used from ?), :)

syntax_error() {

error "${1} '-${OPTARG}'"

error "You typed: ${CMD_LINE}"

error "${USAGE}"

error "For more details, see: ${0} -h"

exit 2

}

The nice thing about these examples is that they are all boilerplate. You can copy and paste into your new script and have this level of sophistication. The parts you change from script to script are relatively small.

We can still improve on this UX a bit by adding output color; making data stand out from information and errors.

Colors

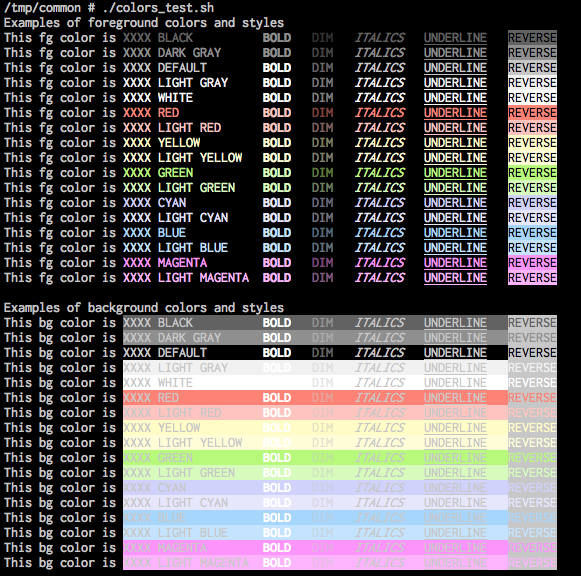

Adding a little color can make errors really standout.

Any modern terminal can display color. The Standard ECMA-48 “SGR - SELECT GRAPHIC RENDITION” section defines how color codes should be implemented and FLOZz’ Colors and formatting article shows how they really work.

The utility_example.sh script uses colors.sh to print simple colors as shown in the code snippets above. It implements simple 16 color but that looks pretty good in our 4MB Alpine Linux container.

colors.sh has a simple syntax that allows changing style within a single colored line or having multiple colors and styles in a single line.

stderr "$(red $(bold 'Red BOLD') and then some $(italics 'italics') or $(reverse 'reversed text') within one red line.)"

stderr "$(red $(bold $(italics $(underline 'Underlined red BOLD italics'))) within one red line.)"

Check out the other color terminal test scripts, run them in your target environment to see how well they work:

common/colors_test.shprovides examples for usingcolors.sh.ux/color_fg_bg_display.shshows 256 color foreground and background examples.ux/color_formatting_display.sh

Note: The last two are borrowed from FLOZz’ page with some fixes to make them work in a Bourne shell.

Communication note

From a design perspective, color is a powerful weapon and with great power, comes great responsibility. Our goal is effective color, but only enough to draw user attention to things they should notice quickly, organize output to make longer displays easier to read. Basically, anything that makes the user’s life easier. But absolutely no more.

Adding help()

Finally, every great utility needs a great help screen. Great means that it has all the information a user needs, is well organized, and familiar. Man pages and the file header in our script_template.sh are nice cues. But we also want it to be easy to edit and thus easy to keep up to date. That’s a nice segue into heredocs.

A heredoc (here-doc) is a multi-line block of text bounded by a label (EOT in the case below), whose format is interpreted literally and that block is redirected to a command. This means that each space and newline is interpreted literally and what you see in the heredoc is what will presented on screen or in a file.

Heredocs are simpler than echo statements to edit and clearer to read. You can include parameter expansions like ${VAR} and functions like $(function_name). You can even redirect to stderr as shown below.

The only down side, is that because every space is printed, we must out-dent to the gutter for proper formatting. The lack of indention is a bit ugly inside a function, but much less so than more deeply nested.

# Define Usage in its own variable for use in validation errors

USAGE="Usage: ${0} -i int [-htf] [-v enum] [-s string] [-l string]... [file...]"

show_help() {

cat >&2 <<EOT

${USAGE}

Example script parsing common command line argument syntax patterns.

Prints parsed arg values and exits.

Options:

-h Help. Show this help message and exit

-f False. Set 'f' off (1). Default = 0.

-i integer Integer. Any integer. Required.

-l string List, [0..n], of non-blank strings.

Multiple occurrences add to the list. Default = none.

-s string String. Any non-blank string.

-t Set 't' on (0). Default = 1.

-v enum Verbosity, one of 'debug info warn error'. Default = debug.

Use as first option to change for remaining script.

file An unordered list of [0..n] existing files. Default = none.

Examples:

Minimal call, showing only the single required arg

${0} -i 1

EOT

}

Note how we send the output to stderr: send the heredoc to cat which is redirected to stderr.

Epilog

Last month’s shell basics and the above command line utility design and implementation tips provide enough knowledge to write some pretty good scripts. Although this article is long, there is a lot more information and examples in the repo.

Next month, we’ll develop our ability to do more inside the script, turning our attention towards predicates, functions, and flow control.