Pipeline Design Pt 2: Designing the build pipeline

TL;DR Define a general Enterprise Kubernetes build pipeline

The first three pieces of a Kubernetes migration are: the cluster, the ability to understand what is going on in the cluster, and the ability to deploy to the cluster. We want each of these pieces to be rock-solid before proceding to the next; each piece builds on the previous and life is much easier when we don’t have to refactor base layers. Also, a nice presentation and reliable operation go a long ways in building confidence in our new platform.

We assume a working k8s cluster. We have already developed a solid logging standard and implemented it in our reference services. Now, we’ll apply the same diligence to a build system. But first, let’s consider the work at hand.

Few developers dream of putting together a build system. It’s complex, tedious, thankless, and other kinds of non-fun. From a business perspective, it’s expensive. There’s the initial design and implementation, infrastructure (VM & bandwidth), proprietary training, monitoring and alerting, on-going bug resolution, version upgrades and bugfixes, and scaling as your product portfolio grows. All of this distracts developers from solving business problems or producing revenue generating code.

I think the popularity of Travis CI, CircleCI, CodeShip, and others show that many companies recognize, and are willing to pay, this cost. It’s a lot easier to outsource product builds than to find good FTEs or contractors. If offloading is an option for you, you should stop reading right now and pursue that.

If offloading is not an option, then let’s set up some goals to guide us through implementation, big architectural questions, and then an overview of a solution using the building blocks described last month.

The goals

I started writing this article as a guide for many scenarios, and that quickly became a long, complex discussion. Instead, I am going to work through a relatively complex situation which should work for the general Enterprise case. The accompanying discussion should help you remove pieces that are excessive.

We have a single goal to provide the guiding light for all pipeline design and implementation decisions:

Increase Business Agility through automating as much of a build and deploy pipeline as possible.

For this context, let’s define Business agility as the time to move a feature from concept to customer hands. Every time we reduce developer work, or increase developer effectiveness, we are increasing business agility. Our pipeline will attack business agility from both directions: we will automate build, deploy, and quality checks and make everything easier to understand and monitor.

There are a handful of other build-related engineering concerns we can facilitate along the way:

- provide uniform application of corporate standards

- provide single implementation of related compliance concerns

- minimize infrastructure costs

- minimize operational costs

The big questions

Given those vague intentions, and pipeline building blocks from the previous article, we have enough to start the next phase: identifying the topology of this build system. A couple of key questions help with this:

- Where is the build system deployed, and where will it deploy to?

- How many separate deployments of each build artifact are required?

- How frequently do we want to deploy?

- How many break points are required? For manual testing, approval, etc.

These questions get at the heart of issues like:

- How automated can this build system be?

- Where do I store build artifacts?

- How do I initiate and approve builds?

- Where do I deploy all the different pieces of my pipeline?

Most enterprises have adopted a multi-tiered production level build strategy. They have expensive infrastructure (databases, orchestrated infrastructure, etc.) deployed in private areas to provide a production-like environment for new code and to isolate pre-production code from production. The most likely k8s migration route is to replicate those environments and evolve during migration, or when everything is inside k8s; where evolution is easier.

This means that you will likely have a dev, pre-prod, and production cluster. If your clients are geographically diverse, you may also have multiple production clusters.

Most enterprises deploy on a two week, monthly, or quarterly schedule. This hints at the use of the different production levels: Daily work is accumulated in the dev environment, at some period before a production release, that code is moved to the pre-prod environment, and then when proven, it can be moved into production.

The dev environment build system can be triggered from a source commit. If the build and testing succeeds, the binary can be pushed to the dev environment since testing should be sufficient to identify bugs and we can stand a bit of turbulence in that environment. This completely automates a source commit deploying to the dev environment.

The pre-prod environment collects work from several groups and provides some soak time for those independent efforts. To provide a bug-fix loop for this environment, and to not disturb the daily dev work, this environment will need its own build system. That system can also trigger from a source commit and push the code to the pre-prod environment on successful build and test. Another complete automation.

The production environment will receive proven binaries from the pre-prod environment; it will not need a build or deploy phase, only a release phase. This phase will include a special, limited deploy, an evaluation, an approval, and full deploy. All of these steps are unique to the release phase and will likely, only be used in this section of the pipeline.

Infrastructure components

Lots of hand-waving above, let’s make that more concrete. Our build system components are:

- GitHub: source code revision control

- Jenkins: source code build, test and deploy

- Nexus: a local shared object store

- DockerHub: a docker image store

- Support libraries: for integration with Slack, PagerDuty, logging, etc.

All intermediate results have caching and audit points: GitHub for source, DockerHub for docker images, and a private Nexus accessible to all environments to cache common java, groovy, node.js, etc., implementations.

Each environment will need a dedicated Jenkins deployment for building and/or deploying. Let’s start thinking about this as a combined process.

Pipeline overview

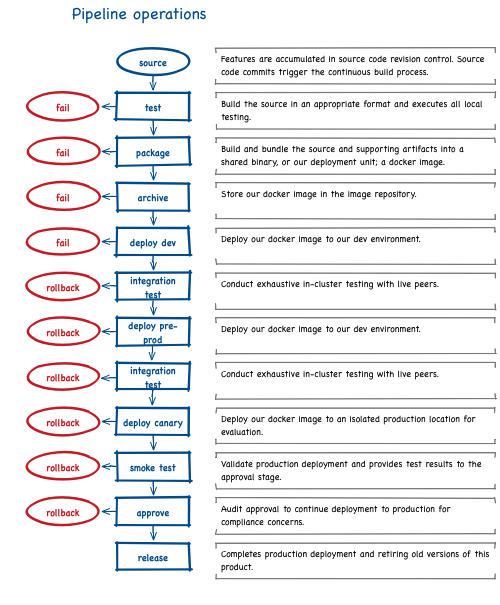

From the discussion above, and reviewing our pipeline building blocks, we can start to piece together an overall flow, for all environments:

Pipeline duties by environment

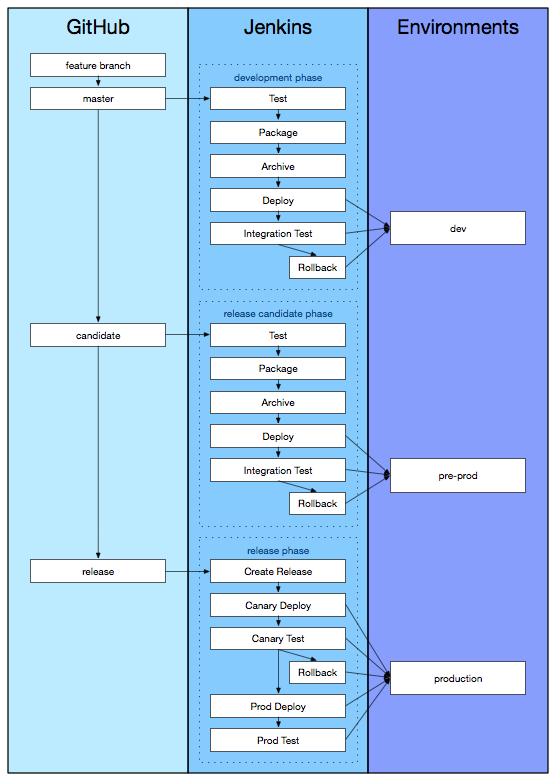

If we squint at the high level flow, we can see some similarities and some differences. We already know that we want to keep the dev code separate from the pre-prod code so we don’t interrupt daily work, or the path to production. We also know that separate work areas, or branches, will make everything easier with Jenkins. To work with common conventions, we will say that these specially named branches will have the following uses:

- master: The master branch accumulates feature branches and bug fixes and is deployed to the

devenvironment. - candidate: The first step in the march to production begins when master is pushed to the release candidate branch and that code is deployed to the

pre-prodenvironment. - release: Production deploys begin with a push from the candidate branch to the release branch. The code is deployed to production in a ‘canary deploy’, evaluated, approved, and then the production release is completed.

Epilog

This is a pretty flexible backbone for our build system. We have adequate separation of work streams, we anticipate that we can handle all of our known concerns, and we have enough wiggle room for emerging concerns. Now we need a little deeper dive into the daily workflow from the developer perspective - something we’ll look at next month.