Choose a ReST framework

Old school enterprise architecture and cloud architecture have different service concerns and value different ReST framework features. Microservices allow you to decouple language choices, so a move to the cloud is a great time to re-think your ReST framework selection.

Background

Developing a justification for microservices takes a while, so I will assume you have already felt the pain of living with an old school enterprise, or monolithic, application and understand a bit about cloud or web scale applications, microservice architectures, or fine grained SOA architectures. If not, see what James and Martin have to say to come up to speed: http://martinfowler.com/articles/microservices.html

In our context, the root problem with monolithic applications is complexity; the core benefit of a microservice architecture is simplicity. Many people are finding that managing one complex application is much more difficult that managing many very simple pieces - why microservices have become so popular in just four years. Each of our ReST framework selection criteria simplify some part of the develop, deploy, support, maintain cycle.

Adopting microservice archtecture requires some mind-shifts:

- Value organizational speed over efficiency

- Choose infrastructure components to simplify required code

- Design data stores to simplify code

- Provide primitives in relational data stores instead of code

- Consider all of dev-ops instead of dividing responsibilities between different departments like development, DBAs, operations, and support.

- Value lightweight components that do one thing well over monolithic components that are everything to everyone

When you make these shifts, you will spend more time in design to simplify and eliminate code. When you no longer need complex domain logic in your middleware and complex transaction logic because of unnecessary data store complexity, what you value in a ReST framework changes dramatically - exactly what we are exploring.

Goals

At a high level, we want a framework that can produce a least cost implementation of a ReST service, from both a development and operations viewpoint.

- Minimal code

- Minimal implementation

- Fast time to market

- Provide for the client

Beyond that, goal definition becomes a bit circular, with the criteria helping define what is a least cost implementation. As we develop each of the criteria, we will identify what is least effort from a development, maintenance, and support perspective.

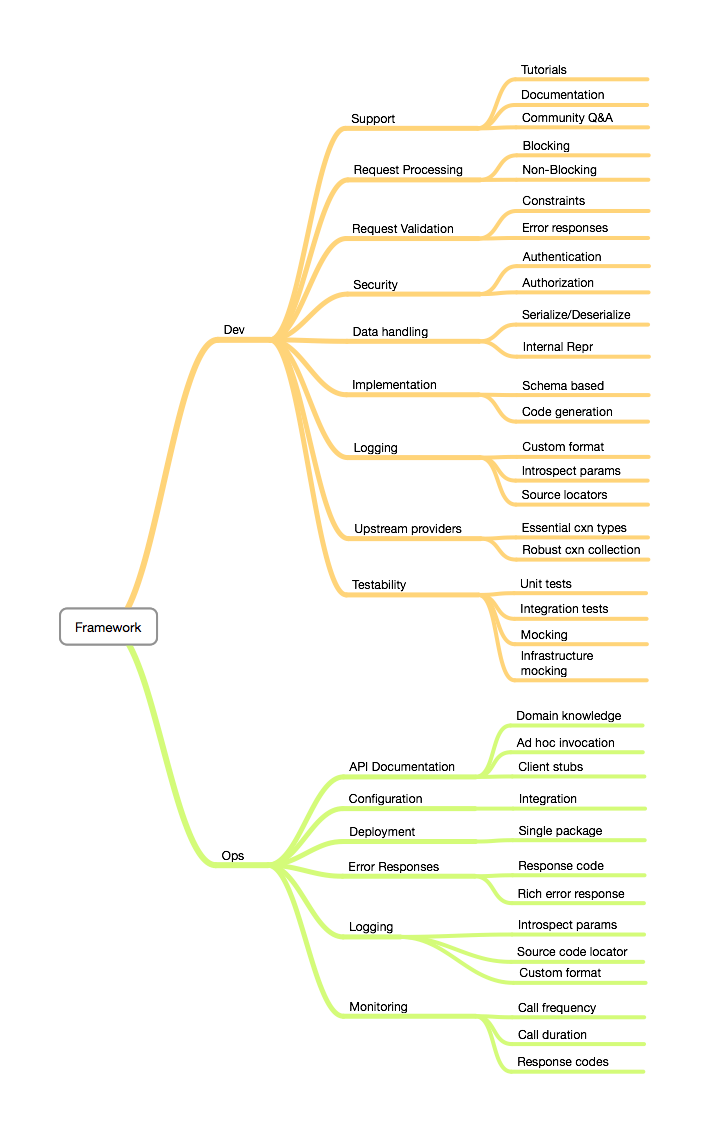

Concerns

Minimum requirements

Each framework should provide a bare minimum of

- Transparent serialization/deserialization

- Request validation

- Integrated monitoring

Support: Documentation and community forums

The driving concern here is ease of use. Some frameworks are very plain and simple to use. Some have many ways of doing the same thing and it can be difficult to piece together the best strategy for a given situation. Familiarity with a language or framework may weight decisions in another direction. This is simply too subjective to compare meaningfully. Instead, we can compare the supporting documentation and you can decide how important that is.

If the framework does not have good documentation and community support, the time you save in advanced features will be wasted on figuring out how to use them. The only thing more frustrating than tedious work is digging through documentation trying to figure out how to use the framework.

Robust frameworks generally provide base documentation, tutorials and example code, and a community support forum.

I value examples over base documentation because the examples show context – how to glue the bits together, and base documentation is a bit like a large picture puzzle. Next most important, a knowledge base of existing questions and answers where others tried to extend the examples or use the base doc – lessons learned from the real world. Finally, an interactive support forum. Why last? Because in general, I solve my problems before I get responses. The existing forum provides immediate answers. However, when remediating a difficult to identify bug, the support forum can save the day.

Request Processing: Blocking vs non-blocking request handling.

Non-blocking services are not new; Java 6 introduced the Servlet 3.0 specification and Spring 4 made it easy to code in the Java world and Node.js derives a lot of its prestige from its high capacity due to its non-blocking model.

Although writing non-blocking code has become considerably easier in recent years, it still requires extra code and attention to introducing blocking calls that will destroy that performance. Once your service starts to hit, say 500 req/sec, this extra work starts to pay off.

You may start writing your service having a realistic expectation of load and know that the simplicity of a blocking strategy is fine, or that non-blocking will be required. You may also want to hedge your bets by choosing a framework that provides both.

Request validation

Input validation is the ability to qualify request variables and reject them if found lacking. Qualification could be required parameters, field length constraints, composite parameter constraints (either this field or that specified), etc.

In addition to rejecting invalid requests, input validation should generate rich error information, describing each of the fields that failed validation and why.

Finally, the validation system should be easily extendable; you should be able to create your own validation rules for edge cases.

Validation should be through configuration, templates, annotations, or something similarly simple.

Writing homegrown validation is tedious, usually results in uneven application, and should be unnecessary now that Hibernate has provided a solid standard that has been implemented/copied in most modern frameworks.

Security: Authentication and Authorization

Authentication is the process of proving someone is who he claims to be. Authorization is the process of restricting access to appropriate callers.

Authentication should be controlled from your front door. This reduces load on your authentication server and allows changing authentication schemes, or supporting multiple schemes, at one place instead of throughout all of your code bases.

Offloading authentication to a web proxy server assumes that the proxy exists on your application/service stack boundary and that boundary is secure. Much the same assumption you make for SSL offloading.

Consider the alternative; requests are authenticated in your code. Where is it authenticated? At the application layer? At the mid-tier? At the service layer? All three? You start to see the problem: duplicate code at every layer requiring coordinated code base changes and a 3x increase in authentication calls.

Authorization, on the other hand, must be done at the access point. The application layer must restrict access to features based on authorization. The services may have to authorize as well, if there are clients other than the application that can access them. If you know that the only access is through an application and it can appropriately restrict access, you don’t care about authorization, but be wary of what you “know”.

Authorization should be implemented as simply as possible, through annotations, schema, configuration, etc.

Data handling

How is data is handled from the wire to the service code to the upstream provider and back again? Since all modern frameworks have transparent serialization and deserialization, this leaves internal data handling to compare.

Some frameworks serialize inbound parameters into an intermediate representation. In Java, this is an annotated POJO. Others serialize data into a hierarchical map representing the inbound JSON. The difference is usually the language: traversing an object map in Java is tedious while in Groovy, Ruby, Python it is trivial. This begs the question: How does the intermediate representation serve us? Is it simply a consequence of a language choice?

POJOs offer some code clarity but is that worth the effort required to create and maintain them?

Implementation simplicity

How simple is it to create a new service?

Spring + Jersey service implementations separate concerns into

- ReST – API definition, validation, error response handling

- Service – orchestration of upstream providers

- Upstream providers – managing outbound calls

One of the big advantages of the Service layer is the ability to wrap multiple database calls in a transaction. If we optimize for speed, we make those operations primitives in the data store, effectively eliminating the need for a Service layer.

Other categories have addressed how to simplify input validation, authentication, and eliminate intermediate representations. We have just eliminated the need for a service layer, so what is left? Nothing that requires code to implement.

Templating and configuration are clearly simpler than writing code.

Testability

Unit and integration testing are essential to most coding efforts. Even if we write zero code, we want guard rails to highlight problems in our configuration/template, mappings to upstream providers, or the framework itself.

If our service implementation approaches the zero code case, we can test sufficiently through an external driver and use facilities like Docker for upstream provider mocking to run these tests locally and during CI builds.

Testing frameworks are generally tied to languages, but some have ReST framework integrations that significantly simplify testing within that framework.

If you have to add business logic to the service, you begin to need unit tests and mocking facilies.

What testing support is needed must be evaluated in the context of the ReST framework and the code base.

Upstream providers

Any framework we choose must have connectors for the upstream providers we will use. This collection should be as robust as possible because we cannot anticipate future needs. We don’t want framework limits to dictate infrastructure choices.

Flexible infrastructure decisions allow us to eliminate code.

There are two difficult to define categories here: everything you know you need, and everything you might need in the future. Let’s set a base criteria of a document store, a relational store, a ReST provider, and a SOAP provider. And at a higher level, a large number of connectors

Rich error responses

Rich error responses include tight control over HTTP response codes and the ability to attach additional data to help the client understand what went wrong and how to fix it.

Meaningful response codes clarify the API and its behavior. If, for example, you can return both 500, and 503, the client can tell the difference between a request that will never succeed due to a server logic fault, and one that they should retry later because an upstream provider was temporarily unavailable.

Fine-grained response codes also support rich monitoring dashboards providing error counts and rates and better indicate the actual problem.

Rich error responses improve the client experience, allowing clients to understand the root cause and possibly fix it immediately or create a bug report with details that will allow it to be located quickly.

Rich error responses are required to monitor and manage the service network. We want to be able to configure the framework to return errors that the client can use to develop retry strategies, identify root causes of faults, etc.

Error responses must be configurable, from setting custom HTTP response codes to filling in error details to enable fast fault remediation at every downstream client.

Automated API Documentation

API documentation consists of domain knowledge and API details. There is no way around describing your domain and how to work with it. This documentation forms a foundation the client should easily be able to apply the API to.

The API details documentation is the tool the developer will use to understand manipulating the domain and will come back to time and again.

We have identified good documentation as a key factor in selecting a ReST framework. Likewise, it will be key to your client’s adoption and success.

Frameworks like Swagger have set the standard for API detail documentation. There are competitors, but to be considered, they should provide similar functionality:

- Verb, URI, and parameter bundle definition

- Narrative descriptions

- Interactive test bed

- Client stub generation

Swagger integrates with just about everything. Integrating it with a Spring + Jersey service means a lot of annotations to identify paths, types, parameters, response codes, and narrative. It gets pretty ugly so I have hidden it in the interface files in the past.

If you have never seen Swagger in action, check out this live demo: http://petstore.swagger.io

Frameworks like Node.js loopback generate Swagger doc from the schema you define, leaving only narrative and response codes to write. This eliminates a lot of annotation writing and code clutter compared to the Spring + Jersey case.

Systems like Swagger can generate documentation in the form of brief descriptions, resources, URIs, input and response parameters. This is presented in a slick web app served from your service. It allows clients to read, experiment with your service. Swagger documentation can be generated from a schema/template or generated during a build step by introspecting several languages and frameworks.

If you can automatically generate documentation in this detail, you can also generate client stubs. Clients that use intermediate representations will find this a great benefit. Some manner of client stub generation should be provided whether it is Swagger, WADL, or RSDL.

Great APIs take good care of their clients. A robust system like Swagger also provides an ad hoc test bed and client stub generation. Swagger already covers many languages and frameworks so the question is likely: how much do you have to do? In Java, you have to provide annotations on your interface classes and a separate build configuration. Systems like Node.js Loopback infer all that is needed from the schema – which you can augment with domain knowledge.

Simple deployments

What does it take to deploy your service? If it is run from a servlet/application container, then you have to maintain and manage that container. Even if you containerize the servlet/application container, you still have manage that container as you build the Docker image. Ansible would suffer the same need. What if your framework built a single deployable package that could be run on its own.

Most ReST services don’t really take advantage of any of the advanced features of servlet/application containers – they are overhead. New frameworks like Spring Boot, DropWizard, and Node build a single deployable package.

Robust Integrated Monitoring

Monitoring is essential for

- Traffic analysis, capacity planning

- Performance analysis, identifying longest running services, cascade failure roots

- Failure rate analysis, revealing weak network and infrastructure components

- Outage quantification, how wide spread is a failure

Collecting and reporting these metrics is a bit tedious and is frequently not implemented. This is a catastrophe for operations leaving your customers to identify errors, no way to anticipate approaching capacity limits, little ability to analyze SOA faults.

If your framework does not provide monitoring, you must build your own. On the plus side, if you build your own, it should work on all services produced with the framework.

What are the essential metrics?

- Call frequency

- Call duration

- Response codes

If your monitoring system also logs request and response parameters, you have eliminated the need for logging.

Logging

Logging is essential for monitoring, support, and debugging. It will be provided by the logging facility, the framework, your custom code, and your custom entries. As with other concerns, the less you have to do, the better.

Key log entries are:

- A task guid: a unique identifier that follows task execution from outer most request to response. If services are aggregated; one calling another, the same task guid should be used for all actors playing a part in completion of the task.

- Request parameters: All request parameters should be logged so you can recreate the call for debugging.

- Response parameters: All response parameters should be logged to aid in debugging. Of course you will want to truncate long responses to reduce log clutter, keeping only enough to aid debugging.

- Outbound request/response parameters: if you are deriving parameters to send to upstream providers that do not have the same logging abilities, you may also want to log these to aid in debugging.

- Significant branching decisions: if your code includes logic, you should log branching decisions indicating the attributes that selected the branch.

Essential functionality

- Format matches needs of log aggregator. Usually this means providing a formatted timestamp, delimited key-value pairs, and narrative entries.

- Precisely locate the log entry generation point by class and method, file and line, etc.

- Log parameters as key-value pairs.

- Log complex parameters as key-value pairs; objects, maps, etc.

- Log narrative entries to allow the author to provide more context around decisions, etc.

If the base functionality is not provided by the logging facility or ReST framework, one or the other must be extensible or you will have to manually add log lines – more needless work.

The least amount of logging required is the highest goal. This is determined by your ability to choose data stores and monitoring integrated into the system that will make boilerplate entries for you like call duration and frequency. When you have to log, it must be consumable by the log aggregator (ELK, Graylog, Splunk, etc.) This is really a go-no-go choice: the framework provides all facilities or it does not.

Feature Prioritization

These features simplify so much that I consider them essential

- Quality documentation – ease of use, implementation, debugging

- Request validation – eliminates validation code, error response generation

- Native JSON handling – eliminates coding/maintaining intermediate representations

- Schema based service definition – transforms writing service code into writing meta data

- Integrated monitoring – eliminates metric collection and logging around normal and exception code paths

These features are all desirable but, if missing, don’t have quite the impact of the first group

- Simple authorization – if the service must authorize, it should be annotation or schema based

- Logging for the log aggregate – able to log complex parameters in a way that a log collection system understands

- Robust upstream connector collection

- Robust testing facilities

- Automated client API documentation including test bed and client stub generation